Elephant Still In The Room 10 Years On From Nia Glassie

Media Release 3 August 2017

Media Release 3 August 2017

Family First NZ says that 10 years on from the horrific death of little Nia Glassie which shocked the nation (3 August 2007), there has been little change or improvement in child abuse statistics because we haven’t tackled the ‘elephant in the room’ – family structure, and the growth of child abuse which has accompanied a reduction in marriage rates and an increase in cohabiting and single-parent families.

“As our recent report on child abuse revealed, there are certain family structures in which children will be far more vulnerable. Suspension of fact is an abrogation of our collective responsibility to children. Children being raised by their married biological parents are by far the safest from violence – and so too are the adults. Until we recognise and develop policies around this issue, we will continue to see the shameful and tragic cases of Nia Glassie and Moko and many others in our courts,” says Bob McCoskrie, National Director of Family First NZ.

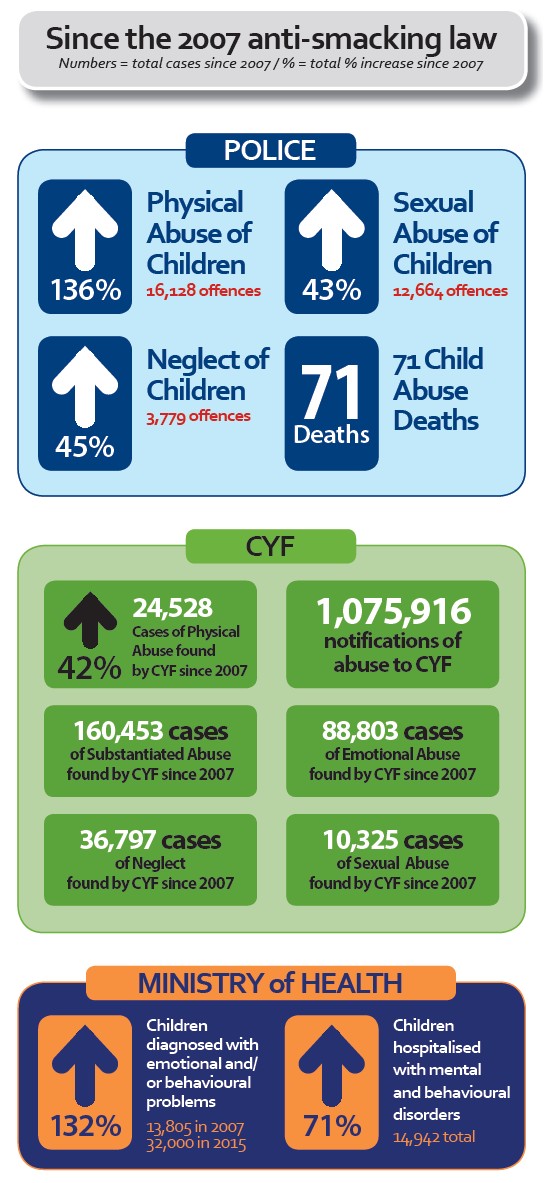

Our stats on child abuse make depressing reading. Police stats show there has been a 136% increase in physical abuse, 43% increase in sexual abuse, 45% increase in neglect or ill-treatment of children, and 71 child abuse deaths since 2007, when the anti-smacking law was passed. CYF have had more than one million notifications of abuse and there has been a 42% increase in physical abuse found since 2007. And health data reveals a 132% increase in children diagnosed with emotional and/or behavioural problems and a 71% increase in children hospitalised with mental and behavioural disorders since 2007.

“The research results are disturbing, but not surprising. The fact that so many social indicators around the welfare of children continue to worsen proves that we simply are not tackling the real causes of child abuse,” says Mr McCoskrie.

“The research results are disturbing, but not surprising. The fact that so many social indicators around the welfare of children continue to worsen proves that we simply are not tackling the real causes of child abuse,” says Mr McCoskrie.

“Our report quotes government statistics which reveal that over three quarters of children born in 2010 who had a substantiated finding of abuse by age two were born into single-parent families. The likelihood of abuse in this family type is almost nine times greater than in a non-single parent family.”

The report “CHILD ABUSE & FAMILY STRUCTURE: What is the evidence telling us?” examined child abuse rates and changes in family structure from the early 1960s through to current day, and concluded:

- For the last fifty years, families that feature ex-nuptial births, have one or both parents absent, large numbers of siblings (especially from clustered or multiple births) and/or very young mothers have been consistently over-represented in the incidence of child abuse – similar to overseas data.

- Maori and Pacific families exhibit more of these features and have appeared disproportionately in child maltreatment statistics since earliest data analysis in 1967.

- The risk of abuse for children whose parent / caregiver had spent more than 80% of the last five years on a benefit was 38 times greater than for those with no benefit history. Most children included in a benefit appear with a single parent or caregiver.

- The high rates of single, step or blended families among Maori present a much more compelling reason for disproportionate child abuse incidence than either colonisation or unemployment, but like non-Maori, Maori children with two-parent working families have very low abuse rates.

- Asian children have disproportionately low rates of child abuse. The Asian population has the lowest proportion of single-parent families.

- The presence of biological fathers matters. Generally, it protects children from child abuse. Marriage presents the greatest likelihood that the father will remain part of an intact family.

- Compared to married parents, cohabiting parents are 4-5 times more likely to separate by the time their child is aged 5. Overseas data also shows a greater likelihood of child abuse in cohabiting families.

Family First NZ is calling on politicians and policymakers to develop policies which support marriage – including free counselling, income-splitting, removal of the marriage tax penalty, tax incentives for stable marriages – and promoting the strong formation of families and preventing the breakdown of families.

“Whenever marriage is promoted, it has often been labelled as an attack on solo or divorced parents, and that has kept us from recognising the qualitative benefits of marriage which have been discovered from decades of research. In virtually every category that social science has measured, children and adults do better when parents get married and stay married – provided there is no presence of high conflict or violence. This is not a criticism of solo parents. It simply acknowledges the benefits of the institution of marriage,” says Mr McCoskrie.

“Governments should focus on, and encourage and support what works. Our children deserve this investment in their safety and protection. Then, and only then, can we can remove the label ‘vulnerable children’ and see the end to cases like Nia Glassie.”

ENDS