The hard lessons of legal marijuana

MercatorNet 20 April 2015

MercatorNet 20 April 2015

In recent years, several US states have legalised marijuana for recreational purposes. This has happened after many years of legal access to marijuana as medicine in those same states.

It has been an unsurprising transition when viewed from at least one perspective, even though from another it is entirely odd.

The reason the transition was anticipated is because changing the image of cannabis by promoting it as medicine is powerful. There doesn’t need to be much nuance in the idea that medicines are good and abstracted from that nasty business of “illicit drugs”. The latter wreck lives whereas the former heal people.

The image change gets into the collective consciousness and people start to think differently, gradually allowing a medical paradigm to overtake even strong contrary evidence of harm. Not everyone has the time to delve deeply, so a cursory overarching framework within which to place the question must suffice for many. Moreover, it is not only those who might actually use marijuana who influence that perception. Moderates, who are unlikely to ever use themselves, are nevertheless an essential part of public opinion and its voice.

This transitional strategy was something recognised years ago by one of the wealthiest supporters of drug legalisation movements worldwide, billionaire financier George Soros. When approached for funding he made it clear he would first support “winnable issues” like medical marijuana. Once they were won the ground would be laid for the main game. Along with others, he heavily bankrolled medical marijuana initiatives in the 90s, and now the fruit of that strategy is ripening.

It always seemed curious that organisations like NORML (National Organisation for the Reform of Marijuana Laws – the acronym says it all), would suddenly become interested in the treatment of MS, glaucoma, spasticity and neuropathic pain. They are not a patient-advocacy group. From the very beginning NORML were only ever interested in legalising marijuana for recreational purposes. Medical marijuana was their beachhead, and at the time all they had to do was stay on message. By focusing on potential medical uses for marijuana, a distorted and simplistic story was hammered home by media savvy operators. Now 23 US states have medical cannabis and a further three are pending.

How strange to promote smoked cannabis as medicine when much of the research on potential therapeutic uses of its active ingredients was still being done, or at best showed only a modest effect. That’s not how modern medical research proceeds for any other potential medicine, so why should it be different for cannabis? In fact several pharmaceutical preparations are readily available, so smoking is unnecessary. Smoking marijuana as medicine is a bit like revisiting opium eating despite pharmaceutical morphine and codeine. That’s 18th century medicine, not 21st.

Moreover, there is a certain irony in the fact that any therapeutic value in cannabis could well be found in elements unrelated to the ingredient that evokes the mind-altering effects. So the medical marijuana movement may have inadvertently been founded upon a non-mind-altering ingredient, whilst paving the way for users to get high on another ingredient altogether.

One reason the transition from medical cannabis to legalisation for recreational use is odd is because it has happened at much the same time as a significant body of research has emerged on how damaging recreational marijuana can be, especially on a young developing brain. The evidence of harm is stronger than it has ever been, and growing. How did that message get lost?

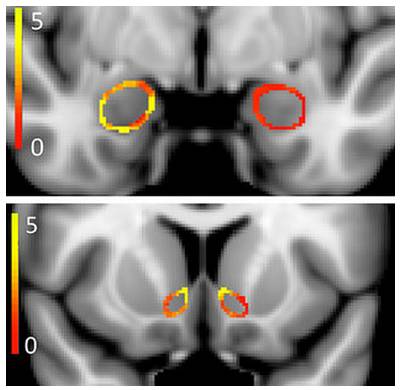

Just last month, work by Hungarian researchers publishing in Nature Neuroscience added to an already disturbing picture about how cannabis has damaging effects on neuronal communication, even at relatively modest doses. Right at the time that communities are becoming more cognizant of a broad mental health problem – some say crisis – an agent that is known to directly contribute to it is endorsed as a lifestyle choice.

Now that four US States have legalised marijuana for recreational purposes, and more could follow, the stage is set for the entry of big commercial operators who will be keen to move swiftly to establish themselves as key product suppliers.

There must be considerable excitement at the prospect of a large new market, especially one that involves addiction. Markets in addictive substances and practices are almost a license to print money. Take poker-machines in Australia for example. It is estimated that approximately half of all revenue is derived from “problem gamblers”. That is, people addicted to pokies who, along with their families and friends, are bearing the brunt of the damage. Or take tobacco. Since over 80% of smokers smoke daily they are likely to be dependent users and therefore represent a guaranteed ongoing market.

Getting hooked is great for business. Someone else’s that is.

Meanwhile, the nascent marijuana industry in the US is taking off. Willie Nelson has started his own brand: Willie’s Reserve; and Bob Marley’s widow and children want us to help “build Marley Natural into a worldwide force for positive change”. I bet they do. The brand-name product will “celebrate life, awaken well-being and nurture a positive connection with the world.” Don’t laugh, it’s serious, as is the money behind Marley business-partner Privateer Holdings.

In reality these are celebrity endorsements that will front hard-nosed businesses that may end up operating much like big tobacco – if it ever gets that far. And as recreational use takes off, we should expect dispensaries for medical cannabis to gradually disappear. Why pay to go see a doctor when you can “self-medicate”?

In Australia, about 1.3% of people smoke marijuana daily, whereas 16% smoke tobacco daily. That 16% figure has come down dramatically over the past few decades and is evidence of an accepted cultural practice being reconfigured because of research about harm. The subsequent shifting social norm has put considerable pressure on smokers. However, having done just about everything possible through education, taxation, social pressure, and various restrictions, the problem, though lessened, has not gone away – by a long shot. 16% smoking tobacco still represents a serious cost, both financial and human.

After all that effort to reduce smoking, what a dumb idea it is to undermine the message by endorsing the smoking of marijuana.

Arguably, as big cannabis and its promotional juggernaut gets rolling, the 1.3% could rise significantly. Not only is it logically consistent that it should increase when restraint is lifted, but in fact that is what happens when more permissive policies are implemented. Holland is a good example. In a paper published in Science in 1997, MacCoun and Reuter chart the trebling in rates as cannabis became available through the “coffee shops”. Notably, the increase was more aligned with ramping-up commercial production than with decriminalisation per se.

If Australia’s 1.3% figure “only” trebled for example, and got to just one quarter of daily tobacco use, the costs, financial and human, would be a far bigger problem than those of tobacco. After all, no one gets stoned on tobacco. Neither does nicotine seem to have anywhere near the disruptive effect on neurodevelopment as cannabis. And trebling could be a conservative estimate.

Addiction to cannabis is real, and most people can recount sad stories of waste and loss amongst family, friends or acquaintances. But just as real is the addiction of governments to the revenue stream. Once that source of income for any addictive substance or practice is embedded they have always found it hard if not impossible to wean themselves off it. For their role in health promotion, it is a conflict of interest writ large.

Despite all the complexity and unknowns about what may or may not happen as cannabis becomes the next “dot-bong”, there is one key question no one seems really keen to raise. That is, what really is the distinction between use and abuse, between a legitimate role or purpose for a substance and its illegitimate use? When does licit turn illicit? Isn’t this the unpalatable moral question, especially when entering an alcoholic stupor (alcohol’s equivalent of getting stoned) is a normalized part of many Western democracies?

Interestingly, that doesn’t seem to be too much of a problem when it comes to some common pharmaceuticals, for example: benzodiazepines like Xanax, opiates like Morphine and Oxycodone, antipsychotics like Seroquel, and amphetamines like Ritalin and Adderall. With these, medicine represents the only legitimate context. Recreational use is not on.

So acceptance by the state that marijuana can be legitimately used for recreational purposes is a major moral statement.

Other countries will be watching the US very carefully. Especially those who have done the experiment and since backed away. It is not wise to ignore them, and to do so will be to learn the hard way.

Dr Gregory K Pike is the Director of the Adelaide Centre for Bioethics and Culture.

http://www.mercatornet.com/articles/view/the-hard-lessons-of-legal-marijuana/15998